Press release written for Bea Schlingelhoff’s exhibition soft mime win at Cherish, Geneva, June 12–August 31, 2020

In an informative blog post, London’s Courtauld Institute of Art speculates that one of the earliest examples of an artist’s signature, in its own collection at least, is Bernardo Daddi’s Polyptych: The Crucifixion and Saints (1348 AD). At the bottom of this multi-panel altarpiece is a line that translates to: “In the year of our Lord 1348, Bernardus, whom Florence made, painted me.”[i]

There are numerous examples of artists signing artworks in Ancient Greece and Rome. The classicist Jeffrey M. Hurwit writes of a very early handwritten artist’s autograph inscribed on the base of a kouros (650–600 BC) by the sculptor Euthykartides. It reads: “Euthykartides the Naxian dedicated me, having made [me].”[ii]

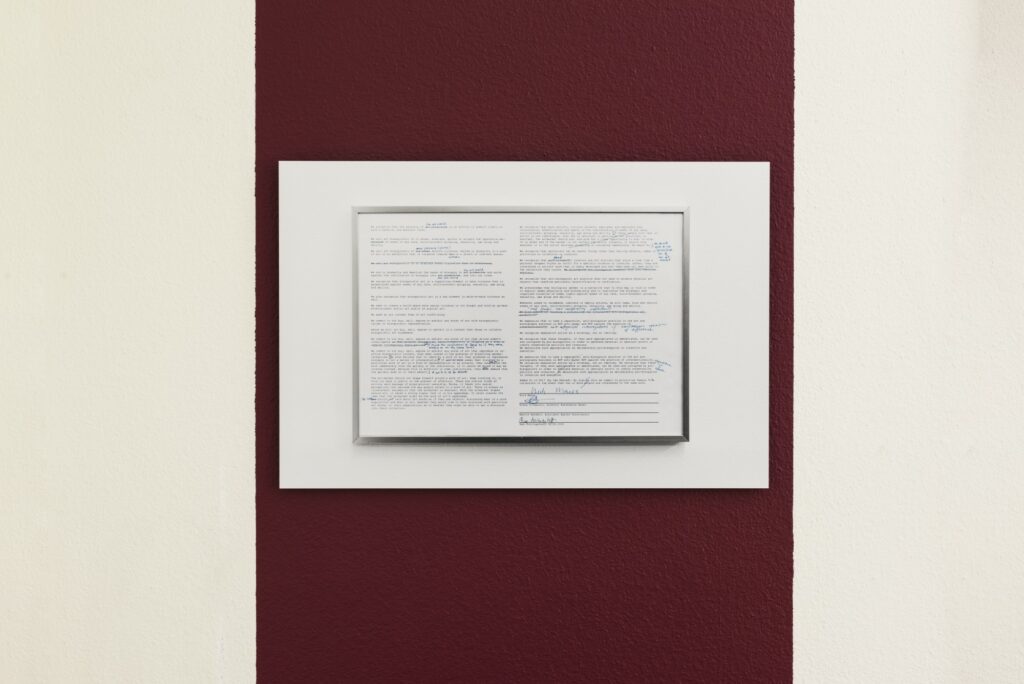

Signatures play an operative role in Bea Schlingelhoff’s softmimewin series, documentation of which is on view in the exhibition soft mime win at Cherish, Geneva.[iii] While early signatures were assertions of origin or devotional gestures, the form has, in the modern period, acquired the status of currency in the international art market. It is this market that soft mime win addresses as its object of critique. Each photographic print in the display depicts a framed document that was included in a prior exhibition by Schlingelhoff, beginning with her solo exhibition Auftrag: No Offence (2017) at Istituto Svizzero, Milan. The two-page text represents a negotiation between artist and gallery director (and occasionally other parties such as curator) over the terms upon which artworks are to be shown. The director is invited to make modifications, largely represented as handwritten notes, to produce a final edit that is signed by all collaborating persons if consensus is met.[iv]

The signatures on each document do not only index the authorship of an aesthetic object (though this function is intrinsically performed) but confront the conditions within which objects and ideas circulate. Women and gender-non-confirming artists have long known this circulation to be restrictive. The experience of seventeenth century Dutch genre painter Judith Leyster, whose signature was obscured so that her portraits could be attributed to Frans Hals, a male contemporary with a higher market value, is one among countless others of the nefarious misogyny of the art market, which Schlingelhoff’s series joyfully and proactively negates.

Yet these are not petitions to grant non-male artists access to the Ruinart Lounge at Art Basel, or other of the so-called privileges of oppression. The negotiations can be read as sensitive deconstructions of the historical relation between gender and subjectivity. Jamaican essayist Sylvia Wynter describes this nexus eloquently when she asserts: “This issue is that of the genre of the human, the issue whose target of abolition is the ongoing collective production of our present ethnoclass mode of being human, Man: above all, its overrepresentation of its well-being as that of the human species as a whole, rather than as it is veridically: that of the Western and westernized (or conversely) global middle classes.”[v] In her writing, Wynter powerfully criticizes modes of economic production that are tied to definitions of the individual human subject. Within the art field, it has been shown that the value of objects is defined by the social relations that are reproduced through its institutional structures. Ambitiously delinking subjectivity from representation, soft mime win attempts to provisionally design—or de-sign—a cultural discourse in which the feminist ethic of interpersonal care is practiced as institutional critique.

[i] “Signed, Sealed, Delivered: A Look at Artists’ Signatures in the Courtauld Gallery.” The Courtauld Institute of Art Blog. September 25, 2014. Accessed June 8, 2020. http://blog.courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/2014/09/25/signed-sealed-delivered/.

[ii] Jeffrey M. Hurwit. Artists and Signatures in Ancient Greece. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2015. 33.

[iii] The series was formerly known as the wimminfesto series. The new title, softmimewin, reflects Schlingelhoff’s interest in the subversive qualities of anagrammatic poetry.

[iv] Michelle Cotton, director of Bonner Kunstverien in Bonn, Germany; Susanne Mierzwiak, curator of Bonner Kunstverien in Bonn, Germany; Joëlle Comé, Director of Istituto Svizzero in Rome, Italy; Laura Becchio; and Martin Hatebur, President of Kunsthalle Basel in Basel, Switzerland each declined the opportunity to ratify the document.

[v] Sylvia Wynter. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation–An Argument.” CR: The New Centennial Review, Volume 3, Number 3, Fall 2003. 313.